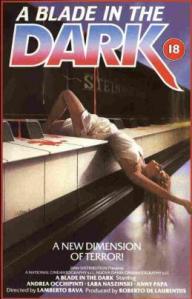

A Blade in the Dark (Reviewed by Lisa Marie Bowman)

If you’re lucky, you remember your first time. I know I do. I was 17 years old and I was trying very hard to convince myself that I was an adult. It had been less than a year since I was first diagnosed as being bipolar and I was still struggling to understand what that truly meant about me. My days were spent wondering if I was crazy or if I was just misunderstood. In the end, I just desperately wanted to be loved. As for the event itself, I remember being more than a little anxious and, once things really got going, pleasantly surprised. However, the main thing I remember is thinking to myself, “Wow, that’s a lot of blood.”

Yes, everyone should remember the experience of seeing their first giallo as clearly as I do.

Over the years, I’ve read a lot of different definitions of what a giallo is and none of them have really managed to capture what makes this genre of film so strangely compelling. The simplest and quickest definition is that a giallo is an Italian thriller. Typically (though not always), the film features a protagonist who witnesses and then proceeds to investigate a series of increasingly gory murders. Often times, solving the murders means uncovering some dark and sordid sin of the past and, just as often, the film’s “hero” turns out to be as damaged a soul as the killer. However, the plot is rarely the important in a giallo film. What’s important is how the director chooses to tell the story. When I watch the classic giallo films of the 60s and 70s, I get a sense of a small group of directors who were all competing to say who could come up with the most startling camera angle, who could pull off the bloodiest death scene, and who could pull off the most audacious tracking shot. Giallo is a uniquely Italian genre of film, an unapologetic opera of mayhem and murder. For the most part, the films seems to have a polarizing effect on viewers. You either get them or you don’t. (From my own personal experience, I think it helps if you come from a Catholic background but, again, that’s just my opinion.)

My first giallo was Lamberto Bava’s 1983 shocker, A Blade in the Dark.

The protagonist of A Blade in the Dark is Bruno, a popular young composer who has been hired to score a horror movie. The film’s director has arranged for Bruno to stay in an isolated villa while he works. Every night, Bruno sits in front of his piano and searches for the perfect note. Occasionally, his actress girlfriend calls him from the other side of Italy and demands to know if he’s cheating on her. He’s not despite the fact that he has two attractive neighbors who tend to come by at the most inconvenient of times and who make cryptic comments about the woman who lived at the villa before him. Bruno would probably be even more frustrated if he knew that, on most night, he’s being watched by someone outside hiding outside the villa. One night, Bruno listens to the movie’s soundtrack and hears a menacing voice whispering on the recording. Meanwhile, the mysterious watcher begins to brutally murder anyone who has any contact with Bruno.

(Despite all these distractions, Bruno continues to vainly try to create the perfect score. Much like Kubrick’s Shining, A Blade in the Dark is as much about the horrors of the artistic process as it is about anything else.)

As it typical of most giallo films, the plot of A Blade in the Dark makes less and less sense the more that you think about it. However, this is a part of the genre’s charm. One doesn’t watch a giallo for the story. One watches to see how the story is told and that is where A Blade in the Dark triumphs. Wisely, director Lamberto Bava keeps things simple. Working with a small cast and one main set, Bava fills every scene with a palpable sense of dread and uneasiness. As Bruno finds himself growing more and more paranoid, so does the audience. Watching the movie, you feel that anyone on the screen could die at any moment and, for the most part, that turns out to be the case.

A Blade in the Dark is probably best known for the brutality of its violence. Even after repeat viewings, the murders are still, at times, difficult to watch. In the most infamous of them, one of Bruno’s neighbors is killed while washing her hair over a sink. The violence here is so sudden and so much blood is spilled (and spurted) that its easy to miss just how well-directed and effectively shocking this scene really is. In this current age of generic cinematic mayhem, the violence of A Blade In The Dark still packs a powerful punch.

(The scene is so effective that, for quite some time after seeing it, I actually got uneasy whenever I found myself standing in front of a sink. A Blade in the Dark does for the bathroom sink what Psycho did for showers.)

Bruno is played by Andrea Occhipinti, an actor whose non-threatening, Jonas Brotheresque handsome earnestness was used to great effect by Lucio Fulci in the earlier New York Ripper. Since I’ve only seen the dubbed version, it’s difficult to judge his performance here. He’s never quite believable as a great composer though you could easily imagine him writing whatever syrupy ballad that James Cameron chooses to play at the end of his next blockbuster. However, Occhipinti does have a likable enough presence that you don’t want to see him killed and that’s all that the film really requires anyway.

A far more interesting presence in the cast is that of Michele Soavi. Soavi plays Bruno’s landlord and, even with limited screen time and even with his dialogue dubbed into English, Soavi is such a charismatic presence that he dominates every scene that he’s in. Before being cast, Soavi was already serving as Bava’s assistant director on Blade in the Dark and, of course, he later went on to have a significant directorial career of his own. Soavi is perhaps best known for directing one of the greatest films of the 1990s, Dellamorte Dellamore.

While Soavi would go on to great acclaim, the same cannot be said of this movie’s director. Among fans of Italian horror, it’s become somewhat fashionable to be dismissive of Lamberto Bava. It’s often pointed out that the majority of his filmography is actually made up of cheap knock-offs that he made for Italian television (and, admittedly, A Blade in the Dark started life as a proposed miniseries). Most of the credit for Bava’s most succesful film — Demons – is usually given to producer Dario Argento. Perhaps the most common complaint made about Lamberto Bava is that he isn’t his father, Mario Bava. With films like Blood and Black Lace, Lisa and the Devil, Black Sabbath, and Bay of Blood, Mario Bava developed a deserved reputation for being the father of Italian horror and Lamberto is often accused of simply trading in on his father’s reputation.

It’s true that Lamberto Bava is no Mario Bava but then again, who is? Blade in the Dark was Lamberto’s second film (as a director) and its a tightly constructed, quickly paced thriller. Bava makes good use of the vila and creates a truly claustrophobic atmosphere that keeps the viewer on edge throughout the entire film. Even when viewed nearly three decades after they were filmed, the film’s murders are still shocking in both their violence and their intensity. There’s a passion and attention-to-detail in Bava’s direction here that, sadly, is definitely lacking in his later films. If most of Bava’s film seem to be the work of a disinterested craftsman, A Blade in the Dark is the work of an artist.